Subscribe

Get OpenSSL Foundation news and highlights direct to your inbox through our monthly newsletter.

Thanks to an investement from the Sovereign Tech Fund, the OpenSSL Foundation has been working a project to "enhance timing side-channel resistance in the BIGNUM code". That's all well and good, but what does that mean? This is the first in a series of posts that explains this project in ordinary English using analogies familiar to people who don't have a technical background. We'll start by answering what "BIGNUM code" is and why it's needed for cryptography.

Modern computers depend on the very simple idea that data can be encoded with a series of binary switches called bits. A single bit holds two possible numbers: 0 or 1. A second bit doubles that number. 8 bits, known as a byte, can hold 256. The formula is multiply 2 by itself as many times as the number of bits. Mathematically, this is called exponentiation. In code it's often written 2^n where n is the number of bits. 64-bit computers operate on a standard data unit (called a "word") that holds up to 2^64 (18,446,744,073,709,551,616) unique values. That's plenty big for most applications. But what if you want to work with a number larger than a 64-bit word?

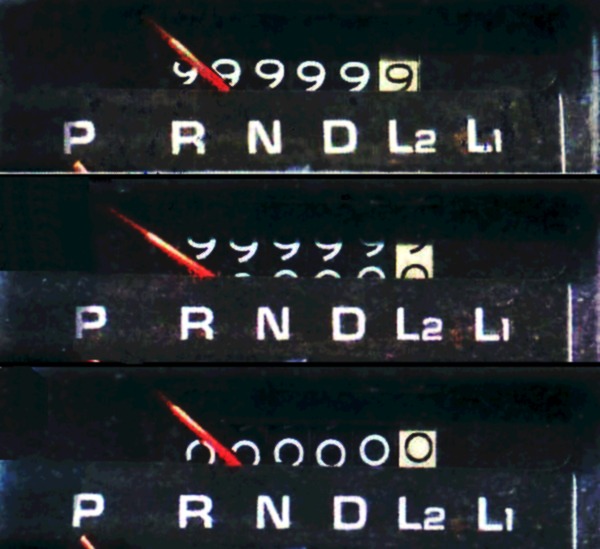

Take, for instance, the number of molecules in a fixed mass of a substance. To do that sort of calculation, you'd need to use the Avogadro constant, which is 602,214,076,000,000,000,000,000. To store that number would require 79 bits. Trying to put it in a 64-bit integer would result in an integer overflow similar to rolling over the largest digit in an odometer:

Instead of storing large numbers in integers, software usually uses floating point numbers based on scientific notation:

m x 10^n

In this format, m is a real number and n is an exponent of 10. Avogadro's number is usually represented as 6.02214076 × 10^23 and that easily fits into the range of a 64-bit floating point number. A wide range of numbers are possible because of the power of exponents.

But that range comes with a catch. Floating point numbers dedicate some bits to represent the exponent (n), which leaves fewer bits to capture digits of the significand (m) portion of the number. Instead of an overflow, the extra digits are rounded off. That's not a big deal for most applications. Nobody is counting each and every molecule in 12 grams of carbon so it's fine to be off by a tiny fraction. But rounding is a real problem for cryptography where every bit of precision matters.

In recent years researchers have cracked public keys as large as 829 bits so the OpenSSL Library needs to handle much bigger numbers than that. While a million bits is overkill, 4096-bit keys are common and key sizes are likely to grow as computers get faster. So the library has used its own arbitrary-precision arithmetic (AKA, BIGNUM) format since the very beginning.

Instead of a fixed number of bits, the BIGNUM format uses an array of bits that can be increased in size to handle larger numbers. To make calculations faster, the OpenSSL Library uses word-sized chunks. So the Avogadro number can be stored in two 64-bit chunks and a 2048-bit key is stored in 32 chunks. Of course it takes longer to do math on larger numbers than smaller ones. It also takes time to allocate more space for bigger numbers. And that has some interesting implications for cryptography.

Next time: why the Sovereign Tech Fund is investing in constant-time BIGNUM.

Odometer image: Hellbus, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Stay up to date with OpenSSL Foundation news and insights

Join our mission to protect global digital infrastructure